Written by Audrey Williams, Zookeeper

The Eastern indigo snake is the longest snake native to the United States, with males reaching lengths of more than eight feet. This non-venomous species is federally listed as Threatened, primarily due to habitat loss. In 2016, the North Carolina Zoo acquired a pair of two-year-old Eastern indigo snakes. By the fall of 2017, they were large enough for their first breeding season. I had been working with this species for over a decade, but this was my first opportunity to be a part of the breeding program! I work in the Cypress Swamp section, where our team has been breeding indigo snakes for three years. Having a leadership role in this breeding project has become one of the most rewarding parts of my job.

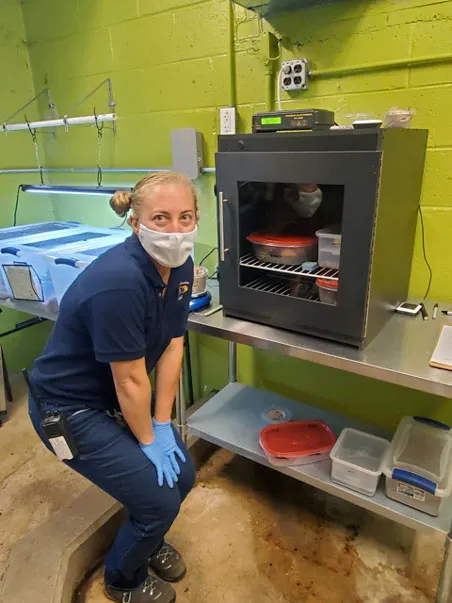

Zookeeper Audrey Williams with incubated Eastern indigo snake eggs

Breeding these snakes is a year-long process. Here at the Zoo, we imitate the seasonal patterns from their natural habitat in order to meet all their physiological and behavioral needs. Predominantly found in Florida and coastal Georgia now, their range once included southern Alabama into Mississippi. In the fall, we begin slowly lowering temperatures and reducing hours of daylight in their habitats. During winter, they become less active and stop eating. Once they are no longer eating (usually mid-November), keepers begin introductions.

This is important because one of their favorite foods in the wild is other snakes, including venomous snakes. If you must swallow your prey whole, what goes down better than something shaped exactly like yourself? For this reason, our snakes have individual habitats. During introductions, behavior is closely monitored for signs of breeding, aggression or stress. Luckily, our couple has always gotten along well. Introductions continue two to three times per week into January. In early March, we begin slowly increasing temperatures and daylight hours in their habitats.

Once it feels like springtime in their habitats, our male indigo snake, Montoya, has fulfilled his role until the next breeding season. Our female, Sarracenia, resides behind the scenes during this time. Keepers create a habitat where she can be comfortable as her eggs develop and are eventually laid. Eggs are typically laid in early summer (April-June). Sarracenia and I both become restless, as she is full of eggs and I am impatiently waiting for her to lay them. Eggs are large and she has laid as many as thirteen! Following egg laying, she is tired and hungry. Keepers increase her feeds and monitor her weight and body condition closely.

Eastern indigo snake eggs

Data is collected on the size and weight of each egg before placing them in the incubator. The eggs remain in the incubator for 90-110 days, where temperatures and humidity levels are checked daily. In early fall Sarracenia is being pampered, but I have grown restless again. Now I am impatiently waiting for the eggs to begin hatching. The young snakes will make a small tear in the eggshell and take breaths, but it may take hours to days for them to fully leave the eggs. As one snake begins the hatching process, the others are stimulated to do the same. The little snakes are weighed and measured before they move into their new habitats. With the eggs hatching in early fall, we only have about a month to prepare for the next breeding season.

Thirteen Eastern indigo snakes currently live at the North Carolina Zoo. Along with the adult pair, we have their offspring--one female, Magnolia, hatched in 2018 and ten juveniles hatched in September of 2019. Snake conservation is my passion, but the most fun part of my job is getting to work with baby snakes daily!

As much as I want to, we cannot keep them all. The Eastern indigo snake SSP (Species Survival Plan) Program manages the population under human care to maintain genetic diversity and will place the offspring produced at North Carolina Zoo in other AZA (American Association of Zoos and Aquariums) accredited institutions, where they will become important members of the population through breeding or education.