Dr. Corinne Kendall, Curator of Conservation and Research for the North Carolina Zoo

Checking my email isn’t generally one of my favorite things to do (and as a program manager I do my fair share of it!), but it is always exciting to see what the birds have been up to. When I was doing my PhD in Masai Mara National Reserve, I would literally receive a text from my tagged vultures, as the units we used in Kenya were based of the GSM coverage, or cell phone system. In southern Tanzania the cell phone coverage isn’t as good and the parks are a lot bigger – Ruaha National Park is about the size of Massachusetts and Selous Game Reserve (which has recently been split into Nyerere National Park and an adjoining game reserve) is about half the size of North Carolina – so we use satellite telemetry. Myself and my team get daily locations of each bird along with some useful tidbits like battery life of the tag, whether or not a bird has changed location in 24 hours, and even information from a fancy sensor that tells us whether or not the bird itself moved (even just twitching from side to side). With vultures it can be tricky. When these scavengers are feeding on a large dead animal – like an elephant or giraffe – they might not go very far for a day or two, so that last sensor can be really important. It lets me know if they are just sitting in one place or if they are dead.

Vultures have few predators and don’t seem to be susceptible to many diseases, yet Africa’s vultures are in big trouble. That’s why I’m constantly making sure our birds are still alive. Poisoning, mostly with cheap and easily accessible pesticides, has become a common practice.

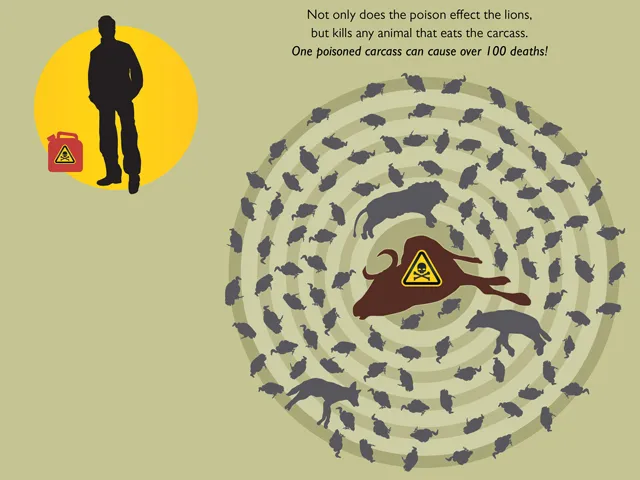

At first, it was mostly being done by pastoralists. The problem stemmed from human-wildlife conflict, starting with lions or hyenas occasionally killing a cow or goat. The owners would be frustrated – that can be a big loss financially – the difference between sending the kids to school or not that year. To fend off these attacks, people would lace the dead cow with pesticides and leave it out for the lions to find. This practice has led to rapid declines in lions and other carnivores. To top it off, vultures would also be killed during these poisoning events – sometimes over 100 birds at one cow carcass. But that isn’t the only poisoning issues the birds face. Poachers also poison vultures. One motivation is the desire to collect vulture feet and heads for which there is an active trade (believe it or not people think vulture heads can help you see into the future – after all, how else could they get to a carcass so quickly?).

The other purpose is to put rangers off their trail. If you are looking for dead animals in a huge park, one of the best ways to find them is to follow vultures – they will be landing and taking off and soaring overhead – a great way to spot a carcass from miles away. Poachers now poison vultures to try and prevent their illegal hunting from being detected. In these situations, a lot of vultures can die quickly. The worst case happened last year, where over 500 vultures were poisoned by elephant poachers in just a few days in Botswana.

So that’s why we have tagged vultures in Tanzania. We track the birds and when one of them isn’t alright, we send out a team to discover what has happened. This will be trickier at the moment with activities being limited in Tanzania due to Covid-19, but there are still rangers hard at work in Tanzania’s extraordinary protected areas, even in these challenging circumstances with the pandemic. If I check my email and have a clear sign of vulture mortality – the sensor doesn’t detect any movement, the bird hasn’t moved locations in over 24 hours, and more often than not, the battery is starting to decline – then we investigate. Getting to a poisoning event quickly is one of the keys to reducing the number of vultures and other scavengers that will be killed. These tags can make all the difference when it comes to saving vultures (and lions) from extinction. Now you might be wondering how we get the tags on the vultures in the first place, but I’ll save that for next time.