Written by Jessica Manzak, Tanzania Giraffe Research Project Coordinator, North Carolina Zoo

Like humans and pets, wild animals are prone to getting sick from many diseases they encounter in the wild. Unlike humans and pets, they don’t necessarily have access to a doctor or veterinarian who can help them get proper treatment to get well again. These diseases can then impact the survival of the overall population of wild animals in an area. Some diseases are mild and may only affect some animals for some time before they recover. In contrast, some conditions can cause many deaths when outbreaks occur. For example, anthrax is a bacterial disease in the environment that exists in a dormant state most of the time. When conditions are right, the anthrax spores come out of the dormant state. They can cause large numbers of wild hippos, zebra, and even elephants to die quickly before going dormant again. Other diseases may not kill adult animals but can cause a decrease in reproductive success. Brucellosis outbreaks in buffalo can cause “abortion storms,” where many cows lose their pregnancies due to the disease. Understanding how outbreaks of different diseases can affect animal populations is crucial, especially if it is an endangered species. When a new disease is spotted, it is necessary to study it to learn how to manage outbreaks.

Giraffe in Tanzania

One such new disease is Giraffe Skin Disease or GSD. In Ruaha National Park in southern Tanzania, GSD was first noticed in the early 2000s, causing patches of hair loss and gray scaley skin on the back and inside of the front legs. Similar diseases have been detected in giraffes in other countries, including large parts of east and southern Africa. However, in other countries, the problems occur on different parts of the giraffes’ bodies. For example, in Uganda, giraffes have very similar skin problems, but they appear mainly on the neck and upper body. We’re still unsure if the same thing causes these different appearances or if they are entirely different. We also don’t know how the disease is affecting giraffe populations. How fast does it get worse? Is this disease deadly to infected giraffes? Does it cause problems with their ability to reproduce? Does it make them more likely to be eaten by lions, especially the giraffe whose legs are affected? All of these questions will determine how important this disease is to the survival of giraffe populations.

Giraffe being monitored as a part of conservation

In Ruaha, around 80% of adult giraffes are affected by Giraffe Skin Disease, so it’s imperative to figure out the answers to these questions. The best way to do this is to follow the progress of both affected and unaffected giraffes and see if there are differences in their lives. The North Carolina Zoo is doing this by keeping track of individuals over time using their unique spot patterns. We track the same individual for an extended period and see how their disease changes, whether they are more likely to be attacked by lions, and whether the females can reproduce. Giraffe #74 is one of our longest-tracked giraffes, with his first and most recent sightings being 978 days apart (just over two and a half years!). He was a sub-adult when we first saw him in April of 2019 and had no signs of skin disease. In December 2021, he was all grown up as an adult and still showed no signs of the disease. Another giraffe, who we call Homeboy but is officially known as Giraffe #16, has been seen the most. We have seen him eight times over two years, and his skin disease still looks the same. Our research so far seems to show that GSD is a very slow progressing disease. However, we’re still working on analyzing our data to see if we can find answers to the other questions.

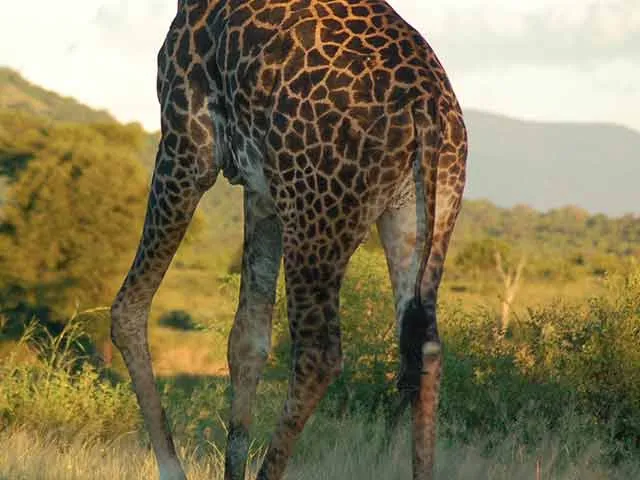

Homeboy's legs

Once we know the impact of the disease on the population, the discussion about what interventions are necessary can begin. As you can imagine, giving a wild giraffe a dose of medicine is much more challenging than giving medications to your pet dog or the giraffe in a zoo! How many times would we need to treat each giraffe? With so many adults already affected by the disease, would we need to treat each giraffe? What would the side effects of any medications be? Could the treatment potentially be worse than the disease if we find that the disease is not causing long-term harm to the overall population? Perhaps the focus should instead be on preventing the spread of the disease to new individuals or decreasing its presence in the environment, rather than curing the giraffes that already have it.

Homeboy the Giraffe

Understanding the effects of emerging diseases on wildlife populations can be essential to improving the conservation management of endangered species. As giraffe population numbers have declined drastically in recent decades, understanding the threats is increasingly important. Giraffe Skin Disease is one of these emerging threats. The North Carolina Zoo’s efforts in Tanzania are working toward answering the critical questions surrounding this disease.